| Barelds - Cycling around the world - Cycle stories - Asia, Africa, Europe, America | ||||||||||||||||||||

| home | site map | world | children | recent | cooking | dutch | german | react | ||||||||||||

Eastern and Southern Africa 1973 (7).

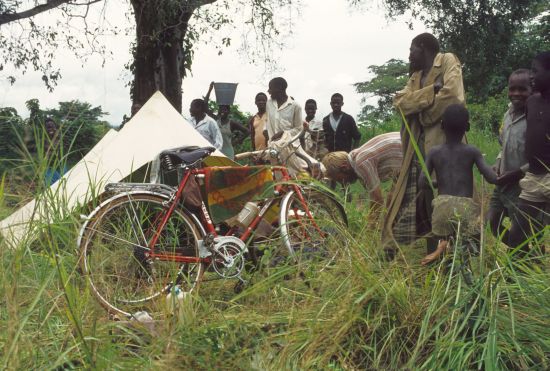

Malawi: Friendly people, but to them you are t.v. until it gets dark, bicycles close to the tent makes even them more curious.

T

hose Frelimo boys have already seen you long ago", said the Portuguese father; where we had put up our tent, "but they have assured me that on this road they have not laid down toys.We had already toiled for days over a country road, partly overgrown, full of mud, potholes and rivers you could wade through, lonely and quiet in a Mozambique that was fighting for its freedom. The main road had to be travelled in convoy because it was strewn with land mines. Whether they would explode under the weight of a bicycle, we rather not tested it. "Here it is safe", assured us the father "but that won't take long".

We had to make long, lonely days, frightening silent it was in the inhabited regions and in the few villages nobody addressed us. Our visa, which was only 5 days valid, had to be renewed in de city of Beira, up to the Pide, the security service. With a broad smile the fat Portuguese stamped our passports: we were indeed the living proof for the outside world that there was nothing going on in Mozambique!!

Nothing at all? When cycling out of the town we passed a junk yard full of army trucks only, which had run on land mines. Further on as far as Rhodesia we now had asphalt under our wheels, it remained silent and lonely however. In the few places you could clearly see why the Frelimo fought for their freedom:

Candy coloured villas with swimming pools for the Portuguese , for the natives huts, not more than a henhouse.

Somewhere in the dense bush we heard the crackle of gunfire. We alighted and looked at each other. "Going on or going back?" When it remained quiet we cycled on and further on we came across an army truck, soldiers around it.

Nervously they pulled the tricker of their automatic "gun-things" and walked into the bush. Surprised, they looked at us nobody stopped us. "Bom dia" we said to them and cycled away as fast as we could, little interested in a meeting between the army and the guerillas. We had heard enough about massacres.

Mozambique: On the dirt roads were hidden landmines, the footpath besides the railway track however was safe.

D

eep down tucked in our hoods against the measly drizzle we came cycling down from the Zimbabwean ruins, side by side but each in his own little lane."Strip roads", the Rhodesians call them, two hardened strips at a distance of a car wheel. In between them, because of the rain, only mud. Loudly hooting a car came behind us, decently Henny rode behind me on my lane, because this is what the law commands, everybody abandons a lane. The hooting continued, increasingly angry, "I am not going into the mud with my bicycle I have just cleaned, you dog". Henny said to himself.

At last the car came alongside us reduced speed lowered his window for a hefty scolding. We looked at him. Bang window closed and off he went. These damned nikkers appeared to be white.

A

lso in South Africa, we soon noticed that, whites do not ride bicycles and we as cyclists were clearly "apart", we were treated as "kaffers". "They scrape the skin from your legs", Henny said whereas in other countries where they are not used to cyclists they always overtake leaving a wide berth. We tried to find as soon as possible country roads: "grond pade" (= earth paths) known as unpaved road and "kronkelende pade" (= winding paths) in the mountains."You will never get through it alive" the whites warned us, "the Transkei is a homeland, only negroes live there". A sad Africa we found there, completely deforested by people who had nothing to live on, a country only inhabited by women, children and old people. The rest worked in the white cities, immigrant labourers in their own country.

It was getting dark and we wanted to camp just like the previous night in a village, where traditionally children, happily talking and laughing sat before our tent. A car stopped besides us. Police. "Don't you want to come with us", he asks it is almost night and there are no campings sites?" "Oh no thank you we will camp in that village over there". "Impossible only blacks live there that is much to dangerous". "Well than we will camp near the police station". "Yes, but" the policeman said, shaking his head "there are only black policemen there".

It took 13 months and 21.000 kilometres, to travel, what originally the "Road to South-America" was. In the Harbour of Cape Town for two months we searched for a ship for the crossing. In vane! The only possibility: sail back to Europe and then to South America, that was too crazy for us.

So we had to fly and as a compensation for our financial misfortune, we didn't have to pay for our bicycles.

| After having cycled for thirteen months we arrived in a sort of Dutch culture: architecture from the 17th century, a language that was simple to understand, was like Dutch, |

South-Africa: The Dutch looking Village street in Stellenbosch. | whites who would like to "gesels" - cosiness - and a social structure; based on a religion pillar structure, well-known to us, had become "apartheid" here. |

| Start World around | Eastern/South Africa | << Previous | Part 5 >> | |||

| Barelds on bicycle through the world - Cycling in Asia, Europe, Africa, America | ||||||