| Barelds - Cycling around the world - Cycle stories - Asia, Africa, Europe, America | ||||||||||||||||||||

| home | site map | world | children | recent | cooking | dutch | german | react | ||||||||||||

Eastern Europe, Near East and Northern Africa (4).

Egypt: Asking the way is not always clear: everybody points in a different direction.

Sitting behind a large, shining bureau he received us, an immaculate dressed gentleman. Stirring in his little cup of Turkish coffee he listened to us. "We come on our bicycle from the Netherlands and would very much like to travel through Egypt, is there not any way to get a permit." What can I do," he said "even the Arabic Diplomatic Corps is not allowed to travel on the road."

In the surroundings of Cairo, of great touristic importance, you were allowed to cycle everywhere. The great pyramids of Cheops, the old step-pyramids of Sakkara, situated in the desert, gave us the opportunity for lovely relaxing trips through the quiet serenity of the desert and fairylike beautiful date palm plantations.

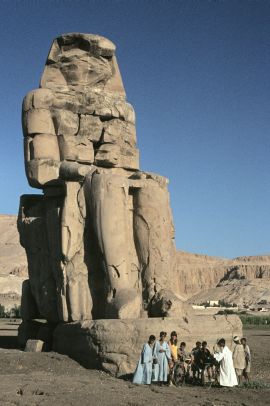

Egypt: Nice little souvenir sellers at the Colossuses of Memnos near Luxor.

"All the same, I want to try," Henny said when we were on our way to Memphis we ran into a large roadblock on the highway to the south.

"Can we cycle on from here," we shouted to the police. Now they shook "no" very definitely.

So we had to take the train. Not the luxurious air conditioned express - they did not take the bicycles - but the slow train, a dusty 18 hours long trip. With regret we saw the indescribable beautiful landscapes gliding past, 1000 km flat, good road, and in between many villages, in our eyes much more attractive than this long train journey. In the cities you saw many, many cyclists. All dressed the traditional pastel coloured galabijas, a kind of long shirt reaching down to their toes. They drifted about on black men's cycles, and they had to make a lot of antics with a slip of their robes in their mouth; to get on or off the bicycle they had to throw the robes across the top tube.

In Assuan, cycling from the station to the hotel, all of a sudden such a fluttering shirt with great speed, crosses the road very close in front us of and hit Henny's front wheel. They both roll on the ground. The fork and front wheel are both distorted. And this in country where we were not allowed to cycle!

We asked our home front to send us a new wheel, but that could at the earliest arrive in Ethiopia. So, with the bent, crushed wheel to the bicycle repairer. In a dark room full of rusty whopping large wheels, he stood there - his galabija full of oil stains - and shook his head. Such narrow fragile rims, no he preferred not to venture this.

In the hotel room Henny went to work himself. Removed all the spokes and straightened the rim, dancing on the ground to stamp out the bumps. Put on the mirror to see if it had flattened already a bit. Put the spokes back again, a puzzle if you have never done it before insert, push it through, up to three times we had to start again before the wheel was a wheel again. I, being significantly lighter, got the somewhat egg-shaped result in my fork "Leave it, you won't notice it on the bumps of the Sudan desert roads which are ahead of us."

Sudan: we were the guests of a police post in Wadi Halfa: Idh-al-Fitr: the end of the Ramadan we had to participate in a great party. The ram is slaughtered for the banquet by policemen in their brand new galabijas.

O

n an old bed without a mattress, in the shade of the unpainted wall, we sit depressed next to each other. We are arrested and sit in the police office of Atbara in Sudan, the bicycles under lock and key, passports confiscated. And what is our crime? We want to cycle so very much!From Assuan we had sailed with the boat across the new Lake Nasser reservoir to Wadi Halfa in Sudan. In Wadi Halfa, the border town, we waited at the police station for 5 days for a permit to travel through the desert. We could go with two cars.

In Abou Hamed - back to the Nile again - we had hoped we could cycle again; the police forbade us and put us on the train to Atbara.

"After Atbara" the Sudanese ambassador had assured us in person "there are roads and villages and you can cycle again".

"How do you continue?" the police in Atbara asked us. "On our bikes" we said confidently. "Impossible, no roads, no water, much too dangerous, you need permission from Internal Affairs" and the whole list was recited again "It looks as if this is not a free country" Henny shouted angrily. Bang! That was said too much. "Six months imprisonment", threatened the commander, "if you ever say that again" and we were taken away.

Sudan: Crow's feet in the sand, sometimes 34 punctures a day, a donkey rider caught up with us every time.

"You should use these bicycles in this country" the railway servant said enthusiastically and put he luggage labels on our bicycles. "We would like to, but he won't let us" pointing at the policeman. Surly he gave us our passports when we entered the train. We whizzed over the road, tailwind, asphalt, the only 190 km asphalt in Sudan and it almost seemed that we could cover that distance in one day. A car, exceptional here, signified that we should stop. We frighten, and dismount, it will not be the police again?. An obese man in a immaculate white galabija, alights, something tinkles in his hand. He replenishes our water. "Faddal" help yourself, a delicious glass cool water, that tastes at a temperature of 40° C (104° F)! "Massalaam", goodbye, he waves.

In Khartoum we had inquired everywhere. The embassy checked it for us, the visa for Ethiopia stood in our passport, it seemed that nothing could bar us that we were going to cycle again. Heavily loaded we left the capital, each had a 2 litre jerry can on his bicycle, 2 kilo of vegetables on the back of the bike, flour, and rice in the bags.

Early on the second day we already soon came on the notorious Sudanese non-roads. "In Sudan", it was said, "the roads are not made for the cars but by the cars".

In the rainy season the broad tyres of the only vehicle that drove here - the lorry - pressed deep furrows in the mud, when dried up stone hard, you could search for the best with your bicycle.

| Start World around | Europe - North Africa | << Previous | Next page >> | |||

| Barelds on bicycle through the world - Cycling in Asia, Europe, Africa, America | ||||||